Eric Gantwerker, MD, gives an interview in which he delves deep into questions surrounding serious gaming and medical education. Among many fascinating topics, he discusses the evolution of teaching and learning in medicine, how technology can add (and detract) value from medical education and the future applications of gaming in medical training.

A term like “serious games” could be read as an attempt to take the fun out of a much-beloved leisure time activity. Serious games indeed are those that are designed with the primary purpose of educating the player. These types of games are used in many industries today, including medicine, and incorporate classic gaming elements like storytelling and simulation. Yet, despite their name, the inherent fun of serious games is part of the reason why they are so effective in helping players learn.

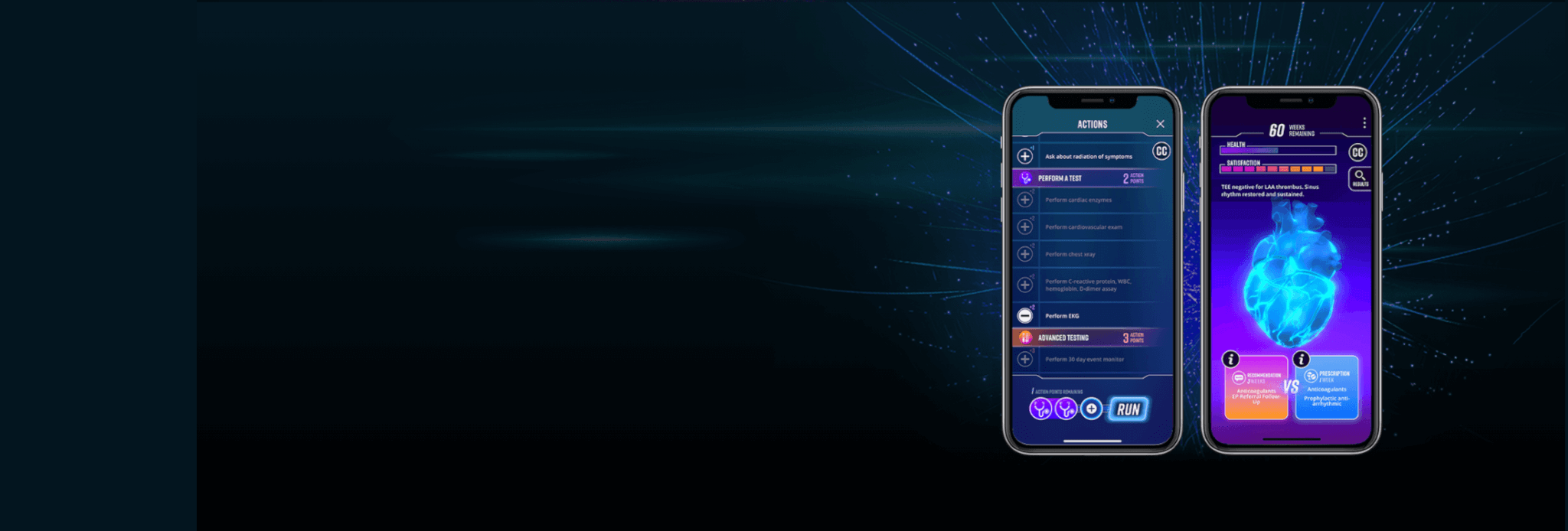

Eric Gantwerker, MD, is an expert at finding the fun in medical education. As the current Vice President, Medical Director at Level Ex, a company that creates video games for doctors, he contributes his vast and unique experience in both education and medicine to developing games that are not just educational, but also spark curiosity. On the clinical side, he’s an academic Pediatric Otolaryngologist who still practices medicine and surgery. His passion for education motivated him to earn a Master’s in Medical Science in Medical Education with a focus on educational technology from Harvard Medical School, which led to him becoming a Clinical Instructor at Harvard Medical School and on to academic positions at UT Southwestern, Loyola University Chicago, and Hofstra/Northwell Health.

I was lucky to interview Dr. Gantwerker to get his insights on everything from the history of medical education to how serious games can help prepare clinicians for pandemics. Read the full interview below.

How has medical education progressed from its beginnings to today?

Medical education was largely an apprenticeship model with no defined criteria or expectations at the turn of the 20th century. These were detailed in the scathing Flexner Report in 1910 that talked about how deplorable the medical education system was. As a result, a large portion of “medical schools” closed and the traditional 2 years of pre-clinical and 2 years clinical education started that persist today. Traditional medical education was set on learning subject matters in blocks (e.g. pathology, anatomy, pathophysiology). There have been recent movements at many medical schools focused on shifting earlier clinical exposure for students and better integrating the subjects across medical systems and diseases (cardiology, respiratory system, etc.), also with more integration of simulation and technology across medical experiences.

Why do you think medical innovation has been classically slow to innovate?

For decades medical education has been slow to innovate and I think this is because of a variety of reasons. One major reason is because people worry about attempting new and relatively unproven innovations on patients. There is some natural trepidation when a human life is involved and the stakes are so high. Additionally, the education system is steeped in tradition. Many people do not see the reason to adopt change when they believe the status quo has seemingly “worked” for so long. Of course, there are also financial factors at play since medical schools don’t traditionally invest heavily in innovation and hospitals run on relatively slim margins.

Do you prefer the term serious games, applied games or something else?

Terminology has been a hot button topic. Some words that have been thrown out there include serious games, gamification, edutainment, games for education, games with a purpose, etc. All these terms have different connotations beyond the meaning they are intended to convey. I know that at Level Ex we tend to avoid all of these terms because we strongly believe that entertainment is front and center and education is the unintended consequence of the fun. In general, I think serious games is an acceptable term for most where people are using game technology and psychology to create learning experiences. The negative connotation is born out of the fact that too many companies have failed to fully capture the gaming principles and instead resort to superficial “gamification” elements from games like competition, leaderboards, or badges. Games have a much deeper psychology underlying why different mechanisms work and one can’t just skim the top and slap it onto a learning experience and expect it to be more engaging or motivating for learners.

“What needs to be taught are the questions you can’t Google,” is something you’ve said in interviews. How do serious games for medical education fit into a world where students have unlimited access to knowledge?

I think “can this be googled” is a very good bar to assess whether it should be taught or not. In a world where students have instant access to information, we must instead teach them how to deeply understand the concepts, how to search out information needed, how to assess the validity of that information, and how to apply it to novel problem solving. Games are built on the idea of presenting players with problems and training them in the skills needed to solve those problems. Games can help create scenarios that allow users free access to base information, but they need to understand how and when to apply that knowledge for given scenarios. They may know that heart failure is treated with diuretics (water pills), but they need to understand how diuretics work, when would it be a bad scenario to give diuretics, and how to handle that patient.

You’ve said that it’s important to spark curiosity to create lifelong learners. How can serious games spark that curiosity?

Curiosity is the hallmark of intrinsic motivation. We need to capture that wonder and amazement that brings people into medicine and make sure it persists across the educational continuum. In my teaching, I use interesting tidbits or random historical facts to tie things together. Things like, have you ever wondered why the water sprays out of the hose when you partially cover it and how the physics behind that can explain heart murmurs and wheezing. Games can easily spark this curiosity by giving scenarios like this that crosslink to connect seemingly disparate phenomena and give new perspectives on traditional teaching.

You’ve cited using smartphone-based audience responses systems (ARS) in your own teaching to engage learners. Why is it important to incorporate the technology students use every day into teaching?

I always joke that I want students to use their phones for good instead of evil. I know that they will be using their phones every day in clinical practice, and they will always have access to this technology. I want to have them leverage these technologies while learning in a way that they would in practice. I often use open ended questions in the ARS that allow learners to anonymously post their thoughts. This is important because it gives every student a voice in the educational experience. Instead of relying on people to speak up in front of their peers, which can be very anxiety provoking for many, they can collect their thoughts and share them anonymously and electronically. This is vital because the hallmark of understanding is being able to package that information into a cogent coherent thought and express it. This allows them to go through that thinking process without the anxiety of public speaking or the fear that they may be wrong.

You’ve said that technology needs to have a value-add in education. How does serious gaming add value to medical education?

Too often I see companies and educators using technology for technology’s sake. They state “I want to use virtual reality (VR) to teach,” and they figure out some curricular element to shove into the VR experience. I think any modality can fall victim to this. I think understanding how each technology can add (and detract) value are vital to knowing how to match the technology to the learning objective. Serious games and gaming in general can add value to teaching through changing the traditional extrinsic motivational factors into more intrinsic or internally aligned motivations and by engrossing them in goals tangential to the learning. People like playing games and the fact that they are learning along the way is a huge plus.

How do you see the generation gap between educators and learners closing?

This is a tough question because it assumes that educators all want to close that gap instead of wanting the learners to conform to the educators’ world view. I have tried to close the gap with a variety of techniques. Technologically, I have tried to teach educators how to use technology in the classroom and encourage them to allow learners to use the technology at their disposal. After all, today’s starting medical students were born in 2000 and never knew a world before the Internet or the smartphone. This has been a tall hill to climb but we’re slowly making headway. The next is by trying to get educators to understand that what worked for them when they were students doesn’t mean that it will work for today’s learners, nor that it was the most efficient way to learn. I focus on how much we have learned about how people learn and point out that the traditional way of medical education is quite antiquated and does not at all leverage these principles. Lastly, I underline the fact that the educator’s job is to get the learners as high on the learning curve as possible in the time they have them. Sitting on a lectern and presenting the exact same PowerPoint lecture they have shown for the last twenty years is probably not going to hit that mark. We live in a world of personalization and students have different needs, wants, and expectations than students twenty years ago.

How can educators become more adaptable today and in the future?

This plays off well from the question above. To be honest. it takes time and energy. As the educator, you must take time to know who your audience is, what they have learned before, what they need to move forward, and whether those gaps are uniform. For me, I start out with open questions about their knowledge around the topic (tell me everything you know about ‘X’). I can then identify strong knowledge areas, misconceptions, and gaps just with one question. Instead of asking for affirmation (which a lot of educators often do), I ask questions that require them to understand the concepts and connect them with prior knowledge or experiences. For example, using the hose and heart murmur example above, I ask, “Why does the water shoot out? What is happening? What does this have to do with heart murmurs and wheezing?” And I actually wait for people to answer instead of asking rhetorically and quickly moving past it. We then talk about laminar versus turbulent flow. The knowledge base is different for every group, so I spend time diving deeper in different areas of the explanation. I then give them novel questions to answer based on the principles we have taught.

Each year 44,000 to 98,000 deaths occur worldwide due to medical errors during patient treatment, according to the Institute of Medicine. Are we already seeing a reduction in medical errors due to serious gaming and other spatial computing simulation technology?

I think it is still too early to tell for serious gaming. Part of this is that the medical education community has not done proper high level (patient outcomes) research on innovative products including games. It is hard to tie patient outcomes to learning experiences early on in education. We definitely see people are learning and liking learning more when using games. For spatial computing simulation, we are seeing a lot more usage in VR surgical planning, patient education, and medical education, but again the studies are a bit sparse. We know that VR surgical planning has changed surgical approaches seemingly leading to less invasive or morbid procedures.

We know that VR pain distraction has really started to take off leading to less use of opiate pain medications during medical procedures and it is my hope this will one day have effects on lowering opiate medication addictions and hopefully deaths. We also now have digital therapeutics such as EndeavorRx (the game) actually FDA approved to treat ADHD in kids, thus obviating the need for prescription medications. We also have VR phobia applications that allow for phobia desensitization to things like spiders, heights, snakes, etc., without the need for medication. I hope that the research on all these products becomes more rigorous and shows some evidence for decreasing the deaths reported by the IOM.

How important is the realism of these games for training doctors? Does it help with their problem solving?

This is a great question, and the answer is… it depends. There are some studies that have shown higher fidelity can actually detract from the learning. The reason for this is the amount of cognitive load spent processing all the information in the environment instead of focusing on the learning objective. Some studies show that higher fidelity can add to the experience by further engaging the user or showing a level of detail required for the learning to happen. If the task or skill requires higher fidelity to meet the learning objective, like seeing a subtle vessel under the skin, etc., then without that level of detail the experience falls short. If, however, the learning objective does not require high levels of detail, like drawing medications from a syringe, then the higher level of fidelity can actually detract and add cost to the development. I think many procedures requiring complex problem solving would benefit from higher fidelity so learners can see something similar to what they would see in real life.

Do you see serious gaming as a way of training doctors in remote areas in the future? What other applications are on the horizon for this type of medical education?

I see huge advantages for gaming technology to train in remote areas and for global health more generally. The games industry is at the forefront of pushing technology to its limits and app based and cloud-based gaming platforms transcend typical limitations seen by simulation and traditional medical education. The idea that learning experiences can be self-contained, self-driven, and accessed anywhere, anytime is where the real opportunity comes. Besides gaming, I think VR needs some time before primetime. Mobile and web-based augmented reality (AR) may be more ready, but those applications still have their limitations. I think smartphone enabled medical hardware, like point of care ultrasound, will have a big impact especially if you combine that with teleconferencing and virtual mentoring. Another area to look to are AI-enabled point of care decision support tools. This can be anything from diagnosing and treating skin disorders to working up any myriad of presenting symptoms based on known algorithms. The biggest, and probably soonest, application of AI might be personalized learning where the platform will dynamically present information and assessments based on student performance. This creates a personalized learning curriculum for each student.

What has the response been from surgeons, both incoming and experienced, to this type of virtual practical training?

Just like any technology or innovation, there is a group of early adopters, those that are super enthusiastic and willing to try out anything. There is also a group of cynics who would be laggers because they don’t believe the hype and need more evidence to sway them. We have a lot of people in the middle and those that are indifferent. I see the excitement more and more though, more so in the clinical space over education. VR and AR in surgical planning and pain distraction are taking hold much faster than any educational experiences. This might be industry driven, as there are more applications that address clinical practice than medical education.

Has the fact that users can earn CME credits worked to legitimize serious gaming in medical education?

I think the fact that content is peer reviewed (a requirement for CME) definitely gives it legitimacy. There is a bar that must be reached when content is reviewed by people in the field who agree that it hits the mark appropriately and meets certain standards.

How can serious games be used to combat pandemics like COVID-19?

The great thing about games is the myriad of topic areas and mechanics that can be applied. Virology and disease spread is a well-worn topic in games. In fact, early in 2020, a game company had to issue an official statement stating that their game should not be used to make medical policy decisions or to set expectations of what might happen in a real pandemic. Joking aside, I think public health, disease spread, and mitigation strategies are easily represented in games and could be used to understand some basic concepts of pandemic control. Games also have a tremendous ability to create shared experiences that can often be talking points about difficult topics like death and ethical decisions that were being made during the pandemic. Rationing of care became a reality in parts of the world including Italy and even parts of the US. Narrative driven games can be used to present these difficult conversations and decisions in a safe environment. Lastly, the mobile and cloud-based gaming technology can be leveraged to create better asynchronous learning experiences and be a better rural and global distribution model than the traditional education materials.