Webinar

Combined Approaches in Frontal Sinus and Skull Base Surgery

Dec 09, 2020

Description

Brainlab invites you to join our live webinar, “Combined Approaches in Frontal Sinus and Skull Base Surgery”, on December 9, 2020 at 4:00 pm CET presented by Prof. Dr. med. Fabian Sommer, Consultant at ENT department, University Hospital Ulm, Germany.

This webinar will cover topics including:

• Frontal sinus and skull base pathologies with combined approaches

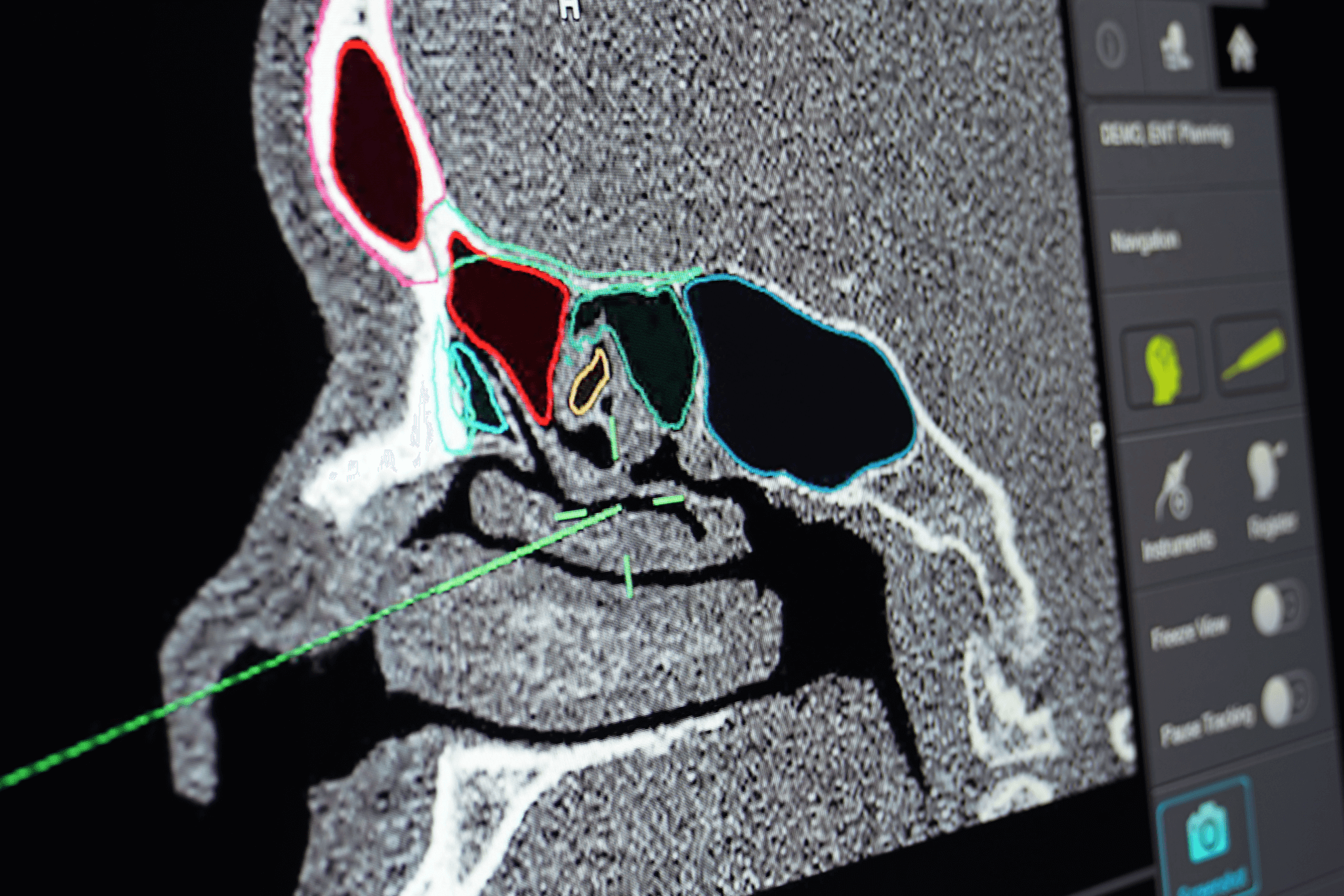

• Intraoperative navigation and its role due to proximity to cranial base and orbit

• Inverted papilloma of the frontal sinus, ngocele/meningoencephalocele, defect reconstructions of the frontal skull base by pericranial flap and “mailbox approach”

We look forward to meeting you online!

Language | English

In case you can not join the webinar, it will be recorded and shared afterward.

Participation is free of charge.

Fabian Sommer, Consultant at ENT department

University Hospital Ulm, Germany